In the last quarter of 2003, just around the festival of Deepavali, some television channels flashed ‘breaking news’ – ‘Insects found in Cadbury’s chocolates’. Around the turn of the millennium, the era of 24X7 news channels had set in. This was one of the first occasions when such an established food brand was in the news for all the wrong reasons. Chocolate being kids’ favourite, and Cadbury being the market leader, the news created immense concern among parents. When the safety of an established food product is publicly doubted, it can create a crisis for the company. Indeed, consumers were deeply impacted, and Cadbury’s business was severely affected. So, did Cadbury’s chocolates really have insects in them? Was a multinational company established in 1824 in England no longer trustworthy?

Genesis of the Crisis

Every crisis has two sides of the story. Let me present both. While the media claimed that several customers found insects in Cadbury’s chocolates, during my interactions, the Cadbury’s Chairman shared the company’s version. A certain shop keeper in Mumbai who had apparently found an insect in a bar of Cadbury’s chocolate was the source of the crisis. The company believed that the bar may have been stored next to some flour or grains and the insect(s) might have crept into it. Instead of raising the matter with the company, the shopkeeper decided to make the matter public. Supposedly, the root of the problem was the shopkeeper’s disgruntlement with Cadbury. He had some personal grievances with the company staff about insufficient stocks and felt that this was the way to express his displeasure. So, he registered a complaint with the health inspector in the Government of Maharashtra.

The October 6, 2003 Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Dept. lab report on ‘insect infestations’ in the Cadbury chocolate bar was positive for the presence of two dead and one live insect. Consequently, the relevant authorities called a press conference and blew up the whole issue before the media. FDA had already seized the chocolate stocks from Cadbury’s Talegaon plant. In its defence, the company released an elaborate clarification statement underscoring the high-quality manufacturing processes followed at its plants, and that the poor storage at the retailer’s end was responsible for the reported case of worms in its chocolates. The FDA did not buy the argument and blamed the company for its poor packaging, which it believed was part of the manufacturing process. In the argument and counter argument between the government agencies and Cadbury that followed, the latter lost sales to the tune of nearly 45 percent at the peak of the festival season.

Proactive Crisis Management

A crisis of this magnitude has the power to threaten the existence of a food company. Readers would recollect the recent case (May 2015) of Maggi Noodles when it was reported that the noodles had up to 17 times the permissible limit of lead content. This was followed by a nationwide ban on Maggi’s noodle products. It was a quarter later, in August 2015, when the Bombay High Court struck down the ban and questioned the procedure followed during the original tests.

In Cadbury’s case, the fight was fought not in the legal courts but in the people’s court. At stake was the trust of three crore consumers who bought the company’s products every month giving it a 70 percent market share. To revive this eroded trust in the Cadbury brand and the safety of its products, the company decided on a multi-pronged strategy to bounce back with ‘Project Vishwas’.

Consumer Education

One of the key elements of Cadbury’s crisis management strategy was consumer education. Under Project Vishwas, it engaged with over 1,90,000 retailers that sold its products. The company proactively underscored Cadbury’s health conscious identity, and invited people to come and see its factories. When interested people came, including media, parents, and students, they were exposed to the rigorous system of quality checking followed on the premises before the products left the factory premises. The observers were convinced that there was nothing wrong in the manufacturing process and the factory ecosystem. The problem arose after the product left the factory. This helped convince customers and the media to some extent.

New Packaging

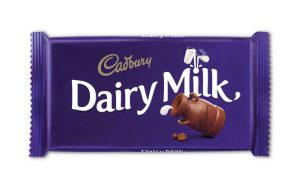

Image: Old Packaging in 1980s and 1990s

Having come face-to-face with a major crisis, Cadbury did not want to take any chances with consumer safety. It wanted to ring fence itself against likely problems in its wholesale and retail supply chain. Earlier, a Cadbury’s Dairy Milk bar used to be wrapped in a foil wrap, which was not sealed. The unsealed foil wrap was packed inside a paper which was open on both sides. This left the product vulnerable to mischief and mishandling. Cadbury decided to revamp the packaging of all its chocolate products. Through extensive discussions, it was decided that metallic poly-flow packaging would be most suitable to protect the product by completely sealing it. This nullified any chance of mismanagement at the retailer’s end. At a cost of over ₹15 crores, Cadbury imported machines that could heat seal the foil and achieve high standards of improvised packaging.

Image: New Packaging from 2004

This process also increased the cost of the product by about 15 percent. However, the company decided to absorb this expense, and did not hike the price of its chocolates. Cadbury’s Chairman Pal underscored the company’s conviction that the product must reach the consumer in the right condition, and if this costs additional money and substantial investment, it should be done.

Constant Communication

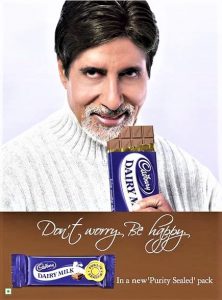

The highlight of Cadbury’s crisis management strategy was constant communication with the masses using the same platform that accentuated the crisis – media. In the consumers’ minds the image of Cadbury’s chocolates had been tarnished. It was natural for any parent to suggest to their children not to buy Cadbury’s chocolates. I recollect another crisis the company had faced a decade earlier when a Lucknow-based scientist claimed that his research revealed that there was ‘nickel’ in Cadbury’s chocolates. While the impact of media in 1993 wasn’t as loud as the 24X7 media of 2003. Yet, I remember my mother advising me (then studying in middle school) not to buy Cadbury’s chocolates! Parents are the biggest stakeholder in the purchase of products meant for kids. Cadbury had to address this vital stakeholder to win their confidence. In the first quarter of 2004, Cadbury increased its advertisement spending by over 15 percent. It roped in Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan as its new brand ambassador. The immense popularity he enjoyed with the Indian masses helped the brand. His deep sonorous voice helped reassure the masses of the renewed measures taken by Cadbury for their and their kids’ safety and wellbeing. The outcome was slow yet positive. After six months of efforts, the demand for Cadbury’s chocolates started becoming normal.

Key Learnings

The consumers gave Cadbury another chance. Market studies indicated that consumers eventually considered the incident as a lapse and not an intentional betrayal of trust to harm consumers. Interestingly, public memory is short; especially for products that enjoy a strong emotional connect with target consumers. Cadbury’s chocolates had been a favourite since 1948 when its products first became available in India.

Nearly two decades later, hardly anyone recollects that Cadbury faced a crisis with its core and most popular product. However, in the current scenario of managing risks and averting crises, Cadbury’s approach of addressing the crisis with a multi-pronged strategy deserves a mention and emulation. Some marketing and PR experts hold the company partly responsible for ignoring the risk to product safety due to inadequate packaging, which could have been proactively addressed much ahead of time, thereby avoiding a crisis with deep financial and brand ramifications. Is it desirable for companies to take such avoidable risks till a crisis emerges? In fact, the best way to avert crises, is to proactively address risks that could cause a crisis.

A key learning from this episode is that a food and beverage company’s responsibility of product quality and safety does not end with the product leaving its factory. It continues till the product is consumed by the end-consumer. Hence, any product quality or consumer safety loopholes in the total value chain should be mapped and proactively addressed by the company.